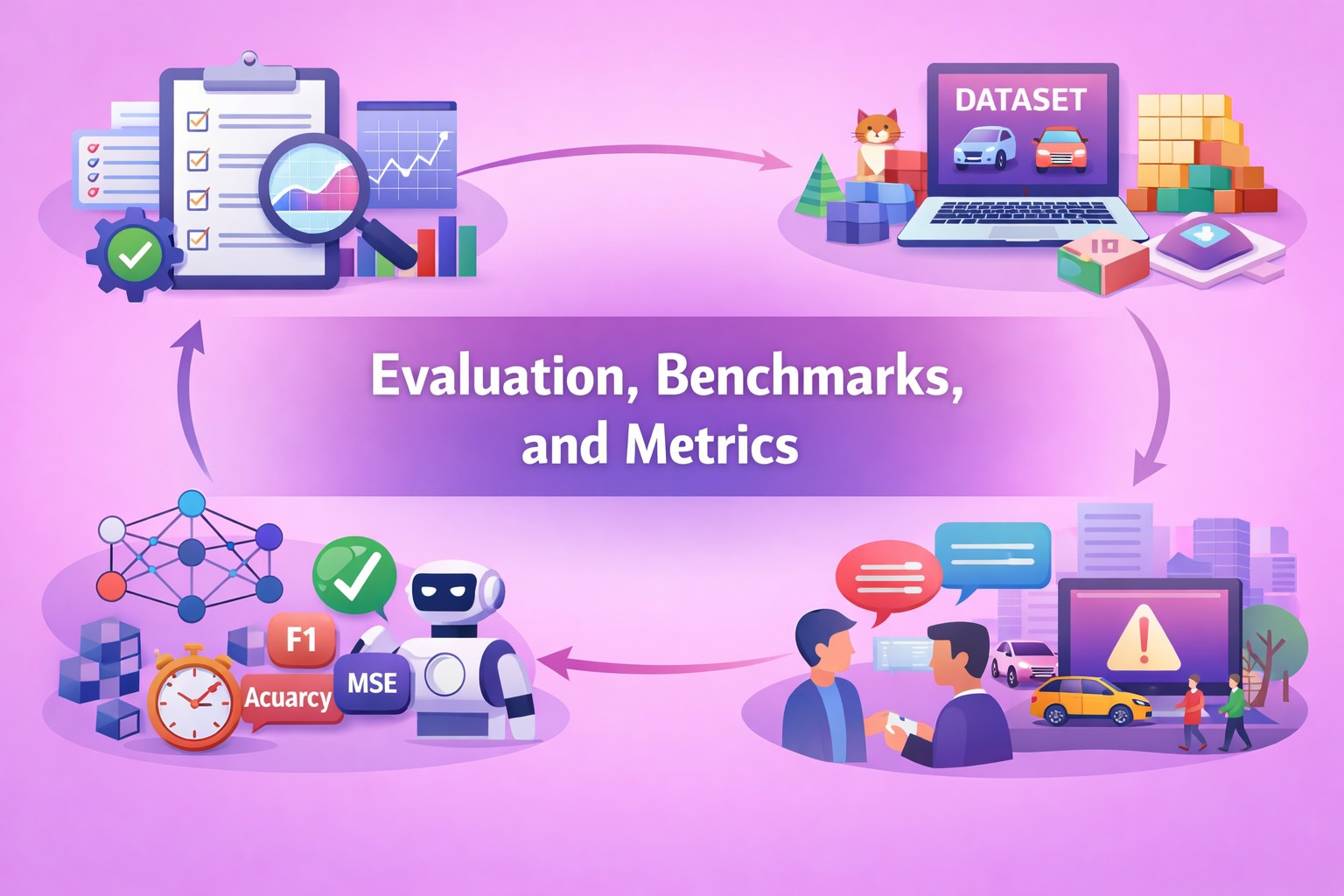

Evaluation, Benchmarks, and Metrics in AI Systems – basics

Evaluation is the backbone of progress and accountability in artificial intelligence. As AI systems grow more complex and influential, understanding how they are tested, compared, and measured becomes essential. Benchmarks and metrics provide structure to this process, shaping not only how performance is judged, but how AI systems themselves are designed and deployed.

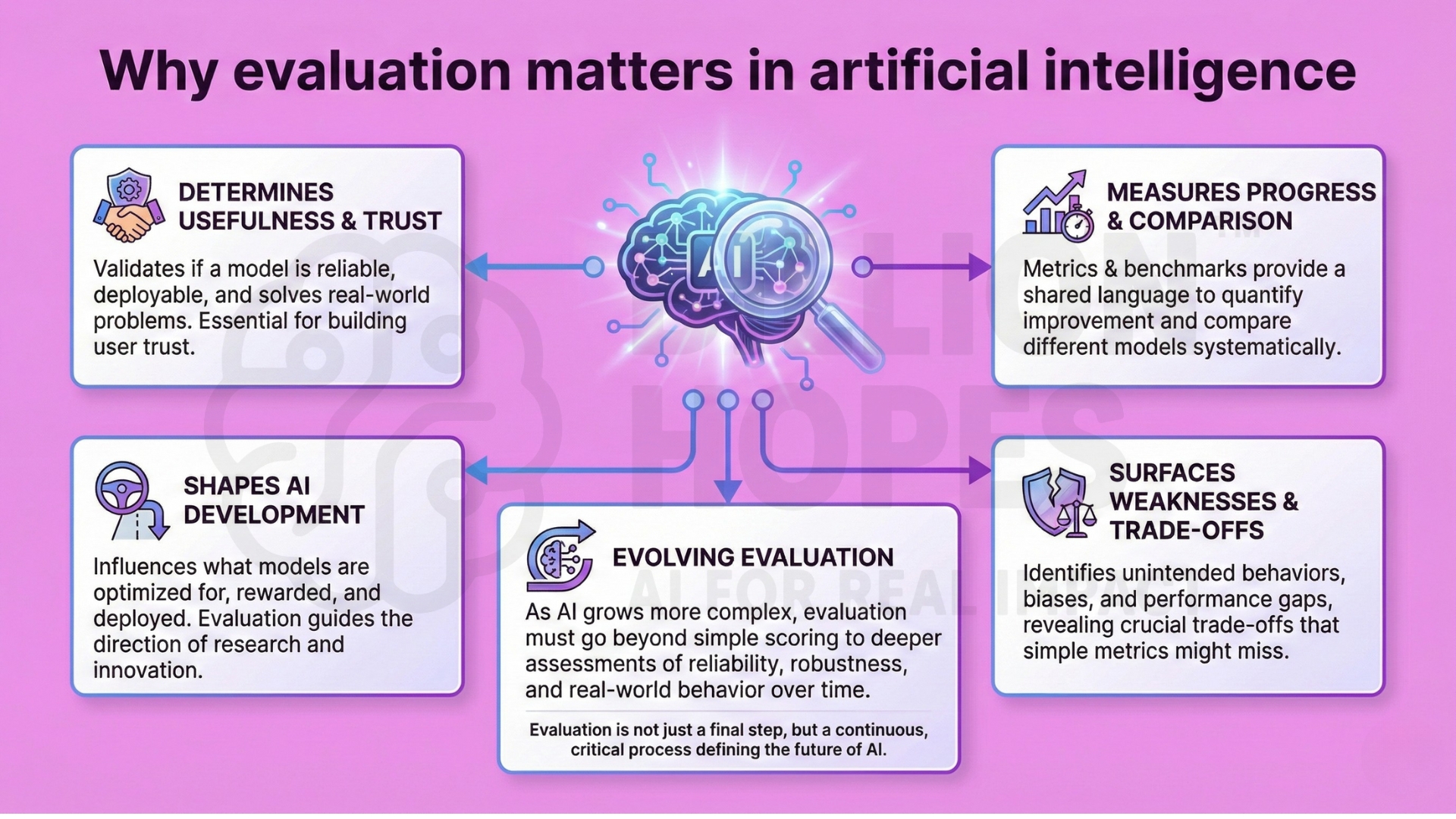

1. Why evaluation matters in artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence systems are defined not only by how they are built, but by how they are evaluated. Evaluation determines whether a model is considered useful, reliable, or deployable. Without systematic evaluation, progress in AI becomes difficult to measure, compare, or trust. Metrics and benchmarks act as the shared language through which researchers and practitioners assess improvement.

Evaluation also shapes the direction of AI development itself. What researchers choose to measure influences what models are optimized for, rewarded, and ultimately deployed. Poorly designed metrics can encourage superficial gains, while thoughtful evaluation can surface weaknesses, trade-offs, and unintended behaviours. As AI systems grow more complex and autonomous, evaluation must evolve from simple performance scoring to a deeper assessment of reliability, robustness, and real-world behaviour over time.

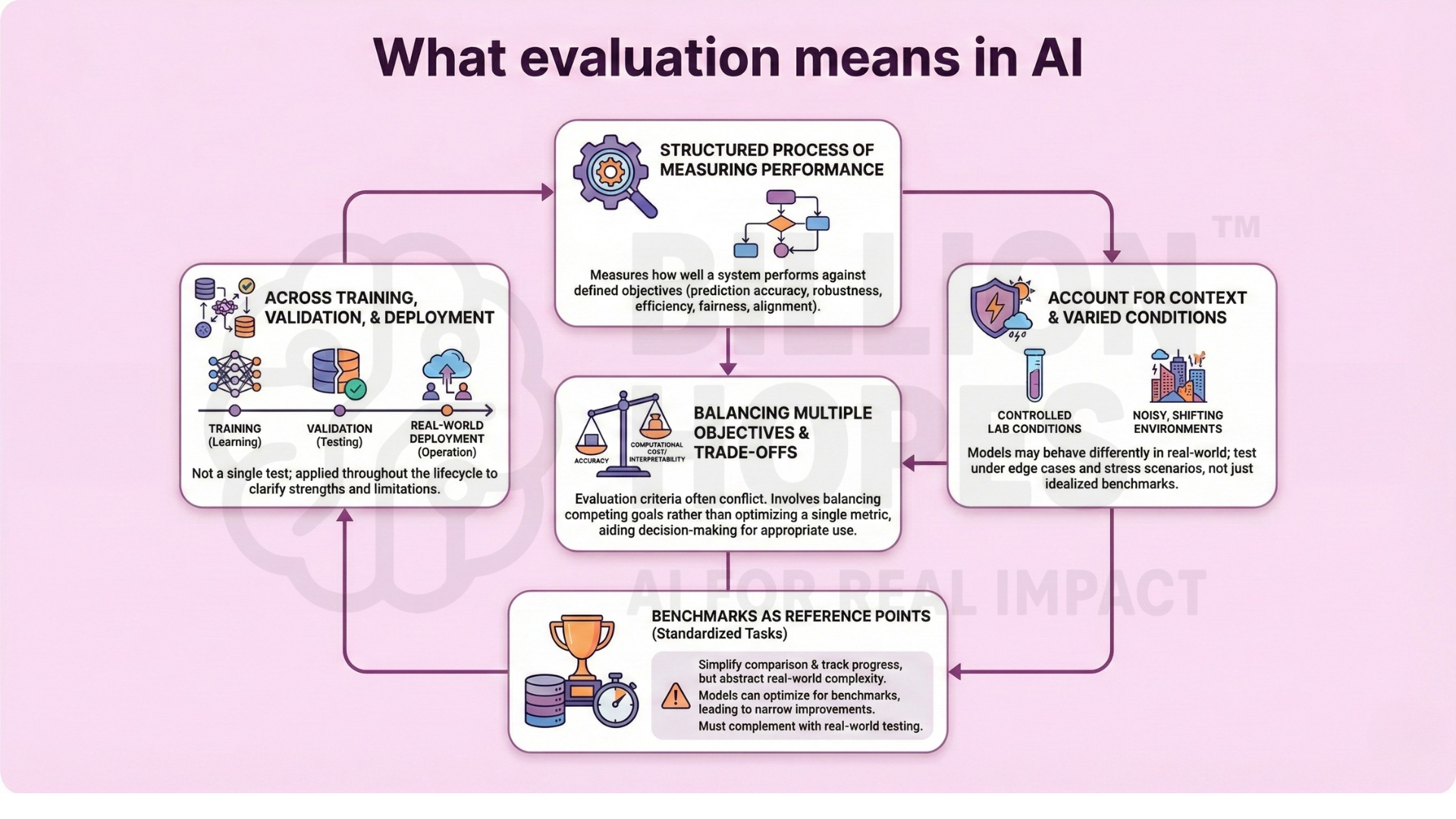

2. What evaluation means in AI

In AI, evaluation refers to the structured process of measuring how well a system performs against defined objectives. These objectives may involve prediction accuracy, robustness, efficiency, fairness, or alignment with human intent. Evaluation is not a single test, but a collection of methods applied across training, validation, and real-world deployment. Good evaluation clarifies both strengths and limitations.

Evaluation frameworks must account for the context in which an AI system operates. A model that performs well in controlled laboratory conditions may behave very differently when exposed to noisy data, shifting environments, or human interaction. This makes it essential to test systems under varied conditions, including edge cases and stress scenarios, rather than relying solely on idealized benchmarks.

Equally important is recognizing that evaluation criteria often conflict. Improvements in accuracy may increase computational cost, reduce interpretability, or introduce new risks. Effective evaluation therefore involves balancing multiple objectives rather than optimizing a single metric. This trade-off awareness helps designers and decision-makers choose systems that are appropriate for their intended use, not just technically impressive. An excellent collection of learning videos awaits you on our Youtube channel.

3. Benchmarks as reference points

Benchmarks are standardized tasks, datasets, or environments used to compare AI systems. They allow researchers to test different models under similar conditions and track progress over time. Benchmarks simplify comparison, but they also abstract away real-world complexity. Performance on a benchmark does not automatically translate into reliable performance in open environments.

Because benchmarks become targets, models often learn to optimize specifically for benchmark performance rather than for general capability. This can lead to narrow improvements that fail to transfer beyond the test setting. As benchmarks age, they may also lose relevance, making it necessary to continuously refresh evaluation tasks and complement them with real-world testing.

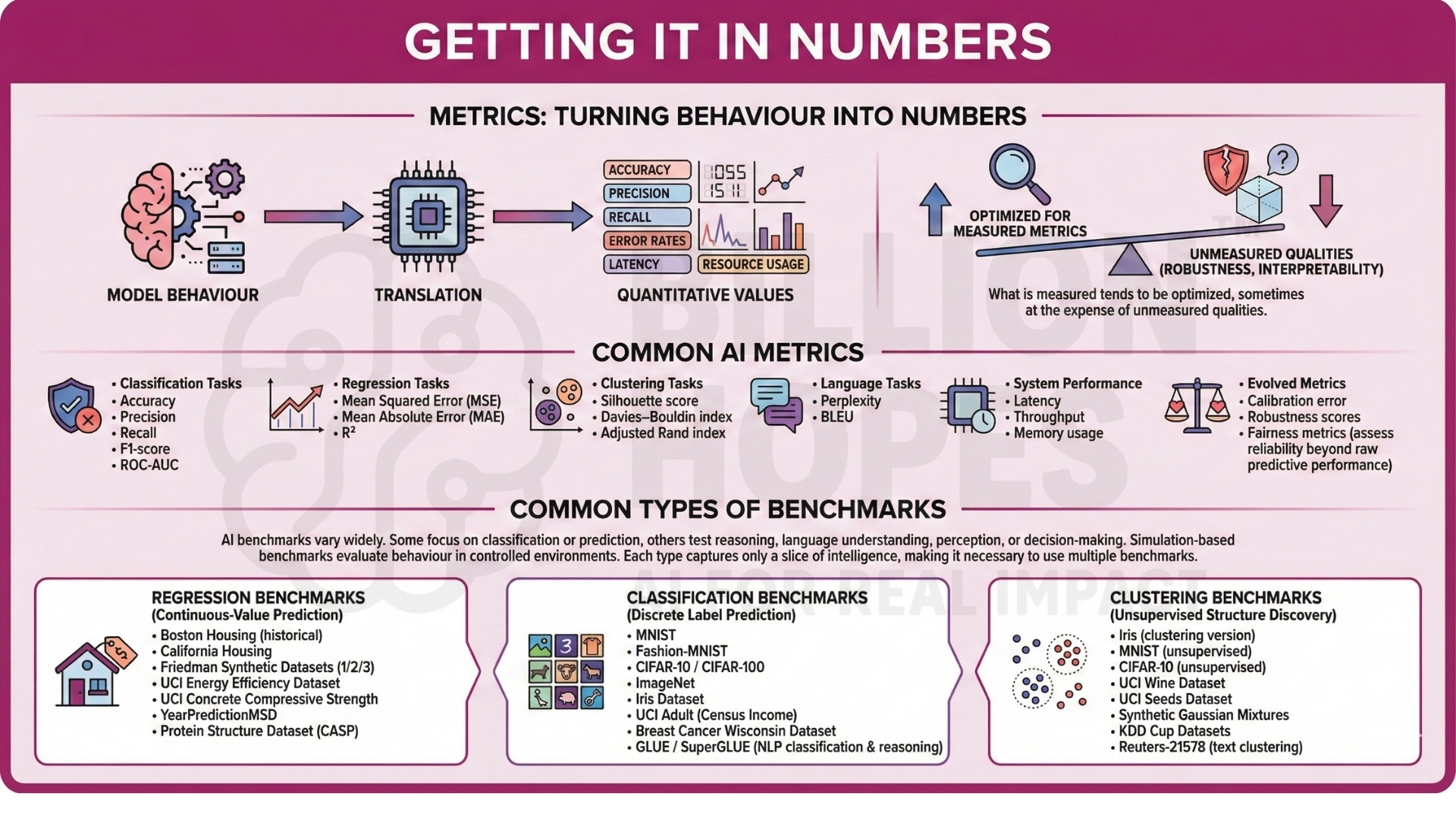

4. Metrics: turning behaviour into numbers

Metrics translate model behaviour into quantitative values. Examples include accuracy, precision, recall, error rates, latency, and resource usage. Metrics make comparison possible, but they also shape incentives. What is measured tends to be optimized, sometimes at the expense of unmeasured qualities such as robustness or interpretability.

Commonly used AI metrics include

- Classification tasks – Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC;

- Regression tasks – Mean Squared Error, Mean Absolute Error, and R²;

- Clustering tasks – Silhouette score, Davies–Bouldin index, Adjusted Rand index;

- Language tasks – Perplexity and BLEU;

- System performance – Latency, Throughput, and memory usage;

- Evolved – Calibration error, robustness scores, and fairness metrics to assess reliability beyond raw predictive performance.

A constantly updated Whatsapp channel awaits your participation.

5. Common types of benchmarks

AI benchmarks vary widely. Some focus on classification or prediction tasks, while others test reasoning, language understanding, perception, or decision-making. Simulation-based benchmarks evaluate behaviour in controlled environments. Each type captures only a slice of intelligence, making it necessary to use multiple benchmarks rather than a single score.

Regression Benchmarks – Used to evaluate continuous-value prediction.

- Boston Housing (historical, now deprecated but foundational)

- California Housing

- Friedman Synthetic Datasets (Friedman 1/2/3)

- UCI Energy Efficiency Dataset

- UCI Concrete Compressive Strength

- YearPredictionMSD

- Protein Structure Dataset (CASP)

Classification Benchmarks – Used to evaluate discrete label prediction.

- MNIST

- Fashion-MNIST

- CIFAR-10 / CIFAR-100

- ImageNet

- Iris Dataset

- UCI Adult (Census Income)

- Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset

- GLUE / SuperGLUE (NLP classification & reasoning tasks)

Clustering Benchmarks – Used to evaluate unsupervised structure discovery.

- Iris (clustering version)

- MNIST (unsupervised clustering setting)

- CIFAR-10 (unsupervised clustering setting)

- UCI Wine Dataset

- UCI Seeds Dataset

- Synthetic Gaussian Mixtures

- KDD Cup Datasets

- Reuters-21578 (text clustering)

6. The limits of accuracy-focused evaluation

High accuracy can hide important failures. A model may perform well on average while failing systematically on edge cases or rare conditions. Over-reliance on single metrics risks creating systems that appear strong but behave unpredictably outside narrow test settings. Evaluation must therefore examine distributions, not just averages. Excellent individualised mentoring programmes available.

7. Dataset bias and benchmark overfitting

Benchmarks reflect the data they are built from. If datasets are narrow, outdated, or unrepresentative, evaluation results become misleading. Models may overfit to benchmarks themselves, optimizing for test performance rather than general capability. This creates an illusion of progress without real improvement.

This phenomenon is often referred to as benchmark saturation, where incremental gains reflect familiarity with the test rather than genuine advances in intelligence. As benchmarks become widely known, models and training strategies adapt specifically to them, reducing their discriminative power. Without continual renewal of datasets and evaluation methods, benchmarks risk rewarding optimization tricks instead of meaningful generalization and real-world robustness.

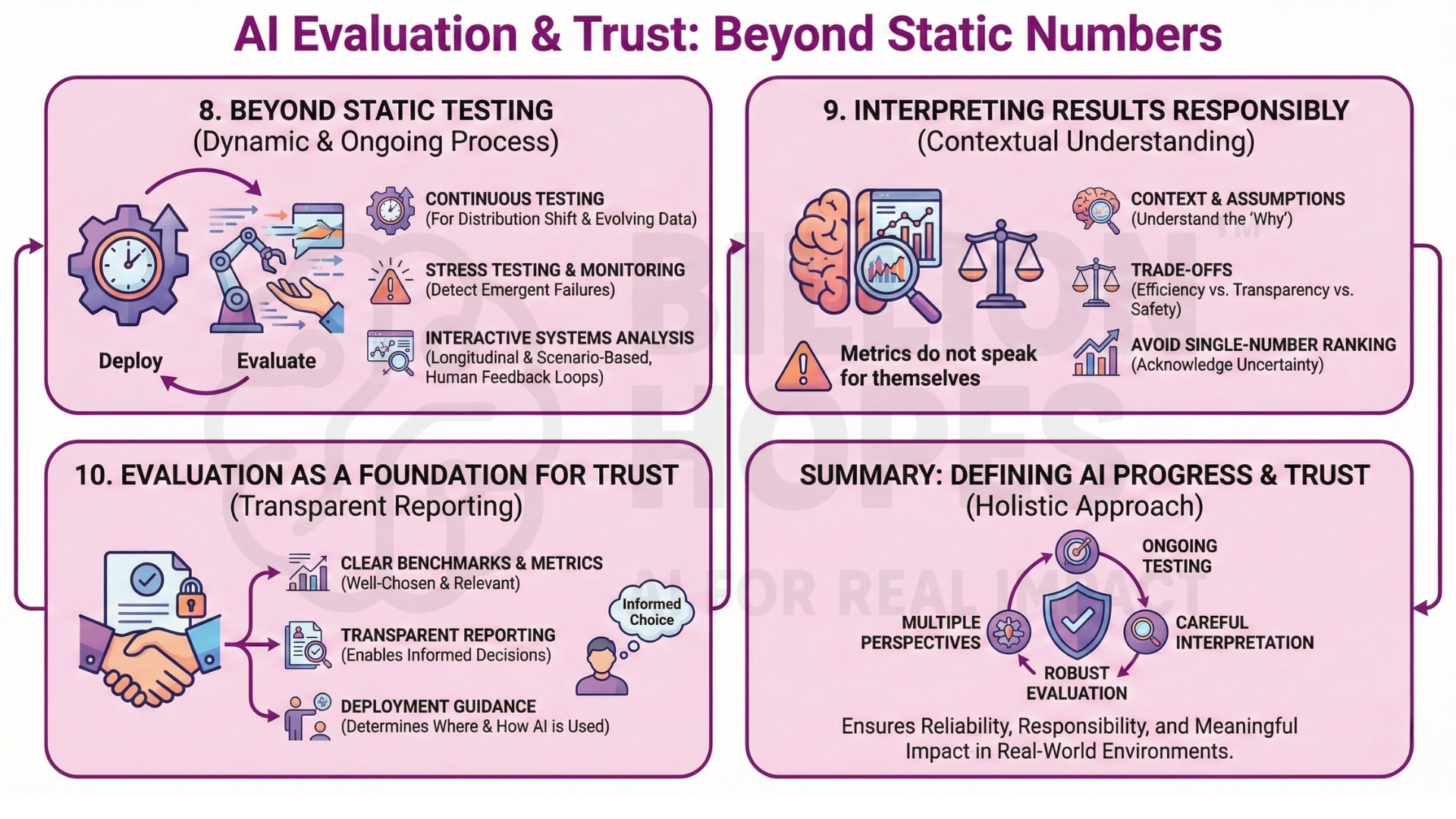

8. Evaluation beyond static testing

Modern AI systems increasingly operate in dynamic environments. Static benchmarks struggle to capture adaptation, learning over time, or interaction with humans and other systems. As a result, evaluation is expanding toward continuous testing, stress testing, and real-world monitoring. Evaluation becomes an ongoing process, not a final gate.

Continuous evaluation allows models to be assessed under distribution shift, evolving data patterns, and changing user behaviour. This helps detect performance degradation, emergent failure modes, and unintended behaviours that static tests cannot reveal. Ongoing monitoring becomes essential for maintaining reliability after deployment.

In interactive systems, evaluation must also consider feedback loops between humans and AI. User responses can shape model behaviour over time, introducing new dynamics and risks. Measuring these interactions requires longitudinal analysis and scenario-based testing rather than one-time benchmark scores. Subscribe to our free AI newsletter now.

9. Interpreting evaluation results responsibly

Metrics do not speak for themselves. Interpretation requires understanding context, assumptions, and trade-offs. A model that scores lower on one metric may be preferable due to efficiency, transparency, or safety. Responsible evaluation acknowledges uncertainty and avoids ranking systems solely by single-number scores.

10. Evaluation as a foundation for trust

Evaluation underpins trust in AI systems. Clear benchmarks, well-chosen metrics, and transparent reporting allow users, organizations, and researchers to make informed decisions. As AI systems grow more capable, evaluation will play an increasingly central role in determining when, where, and how intelligence should be deployed. Upgrade your AI-readiness with our masterclass.

Summary

Evaluation, benchmarks, and metrics define how AI progress is understood and trusted. While they enable comparison and improvement, they also introduce limitations, biases, and incentives that shape system behaviour. Robust evaluation therefore requires multiple perspectives, ongoing testing, and careful interpretation. As AI systems increasingly operate in real-world environments, thoughtful evaluation will remain essential to ensuring reliability, responsibility, and meaningful impact.